The pen that changed the world. Or did it really?

It is not easy to call a product the “gold standard” of a market or sell 100 billion copies of your product to the world. Achieving let alone one of these titles is impressive—it really is the desire for every company. Yet, in the midst of practically every marketer’s journey to achieve such a dream, came with a pen in their hand. A pen that succeeded in achieving not only being the “gold standard” in the pen industry but also getting 100 billion sold to the world that illustrates the miracle in entrepreneurship: the BIC cristal.

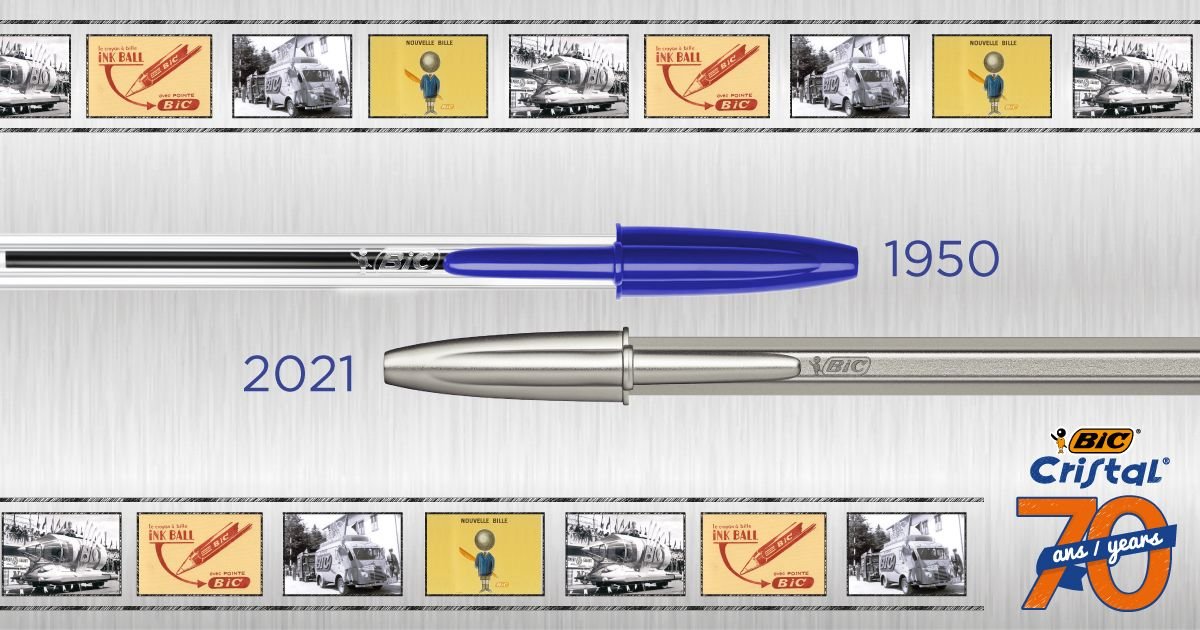

Due to the monotonous designs of pens nowadays, the classic transparent barrel and ink-matching color cap of the BIC cristal is no longer thought of as a wonder. Yet, in the 1950s—when the cristal was released to the world—such a design was a revolution. The ball-point pen, an extremely convenient technology we now simply accept as being “always there,” was in fact what caused the pen industry’s sales to surge over the past decades. László Bíró invented this easy-to-use way to write in ink after seeing how the marbles played by children in a puddle left a trail of water. Following the discovery, working with his chemist brother, the technology was finalized. As elegant as they were, fountain pens were no longer seen as necessary for the everyday customer.

Gaining fame, the ball-point pens were presented at the 1943 Budapest International Fair in 1931 and eventually got patented in ‘38. The brothers’ flee to Argentina with the forthcoming second world war obliged them to found a company far away from their home country Hungary. Yet, as fun as this entrepreneurship journey was, the homemade company was eventually engulfed by the Eversharp Faber company of the United States with a hefty price tag of 2 million dollars. Seeing the pen manufactured in Argentina, entrepreneur Marcel Bich acquired the rights to the company, dropped the “h” in his last name and founded the BICGroup, and later the Société PPA with his business partner Edouard Buffard. Bich continued to refine the shape and functionality of this pen, even taking a bold step to invest in Swiss technology, reducing the ink-hole to one millimeter. With this, history was made, and the BIC cristal was launched successfully.

Nowadays, if one goes to any stationary store, most, if not all ballpoint pens resemble the once exceptional, game-changing design of the BIC cristal from the cap to the barrel—the phrase “gold standard” of pens is not just a phrase. With the boom of this easy-to-use, frugal pen, the so-called pen connoisseurs mock this lack of complexity, claiming that the old, antiquated, fountain pen truly exemplifies the art of writing. Yes, fountain pens do sustain the intricacy that modern-day pens lack, but it is undeniable that ballpoint pens are a wonder, bringing writing into a different realm of easiness.

These conversations often get us swept into the minimalism versus maximalism debate, where the two sides prioritize different things: function for the former and aesthetics for the latter. This yearning for the past—of their elaborate, flowery details—can be an attitude that encourages modern designers to look beyond simplicity. Yet, it is often underappreciated how certain products reshaped our lives—the Cristal allowed for everyone to write with ease, instead of having to worry about buying another costly, cumbersome fountain pen. Despite being a maximalist myself, it is still crucial to recognize the needed harmony between function and aesthetics, for one cannot exist without the other. The rise of BIC cristal, the so-called golden standard for modern-day ballpoint pens, ironically raises the desire for the classic fountain pens to keep the harmony. This seemingly paradoxical debate lingers, as we struggle to find balance in the diverging realm of art and design.